What were Taliban-Era’s impacts on the economy of Afghanistan?

The word ‘Taliban’ has become synonymous with terrorism in wake of the terrorist attacks on September 11. This study challenges the issues behind the word and how it has transformed itself and its meaning in discourse. The past and present usage of the term will be analyzed in the context of the local Afghan political economy and the effects and purpose of US military intervention. The origins of the term will be traced to the destruction of the Afghan economy after the defeat of the Soviets.

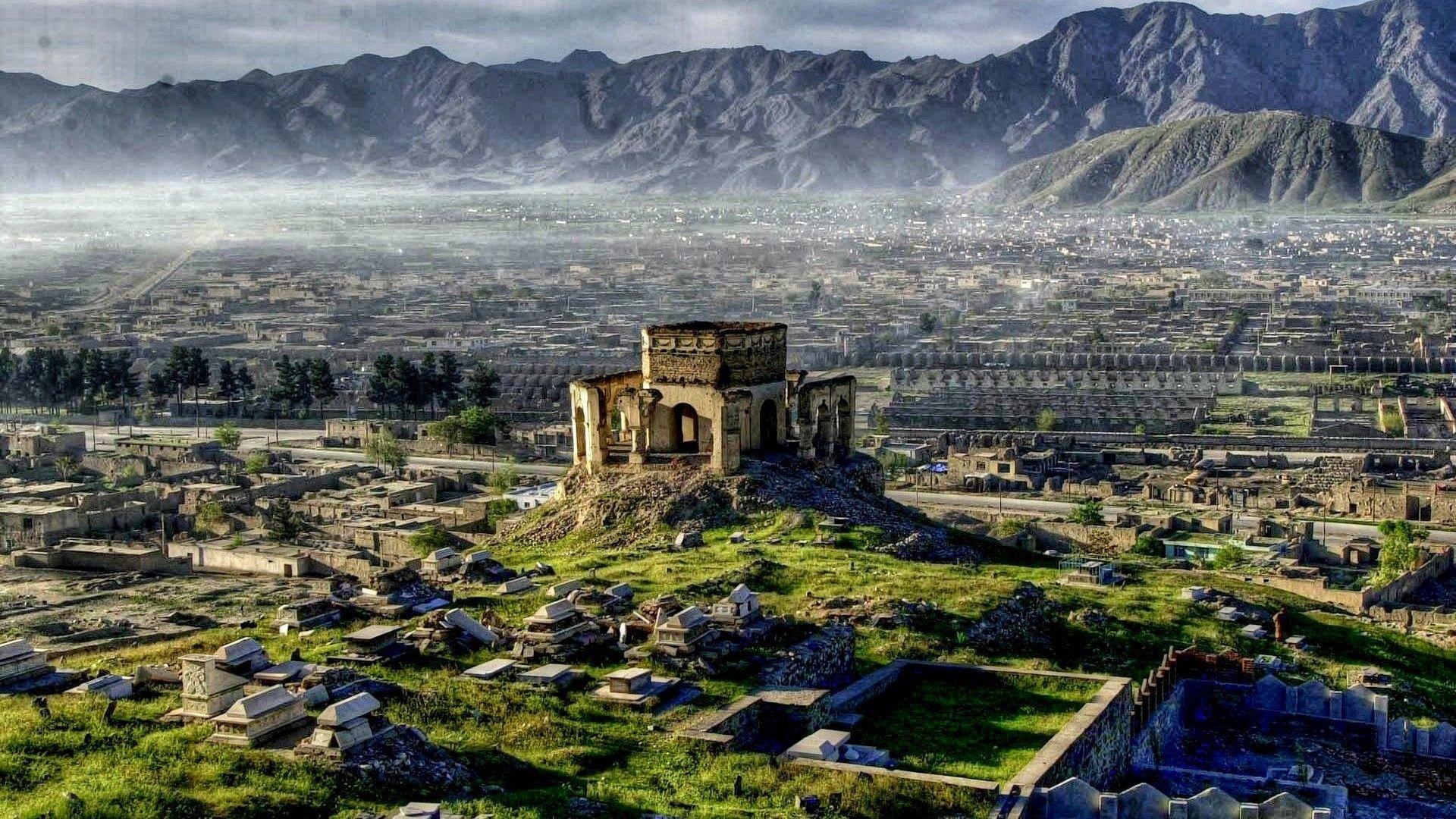

There was no functioning central government in Afghanistan, following over two decades of civil war and political instability. The Pashtun-dominated ultra-conservative Islamic movement known as the Taliban eventually controlled approximately 95 percent of the country, including the capital of Kabul, and all of the largest urban areas, except Faizabad.

A Taliban edict in 1997 renamed the country the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with Taliban leader Mullah Omar as Head of State and Commander of the Faithful. An emirate is a political territory that is ruled by a dynastic Muslim monarch styled emir. It also means principality. An emirate is a subordinate part of the caliphate, if and when one exists. Either the Emir the Caliph might be described as Amir ul-Momineen – the commander of the faithful. There was a six-member ruling council in Kabul, but ultimate authority for Taliban rule rested in Mullah Omar, head of the inner Shura (Council), located in the southern city of Kandahar.

Former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, who claimed to be the head of the Government, controlled most of the country's embassies abroad, and retained Afghanistan's United Nations seat after the UN General Assembly again deferred a decision on Afghanistan's credentials during the September General Assembly session. Rabbani and his military commander, Ahmed Shah Masood, both Tajiks, also maintain control of some largely ethnic Tajik territory in the country's northeast.

Masood's forces were within rocket range of Taliban-held Kabul until late July 1999, but since then the Taliban had pushed them back, capturing large areas. In 1999 the Taliban summer offensive pushed Masood's forces out of the Shomali plain, north of Kabul. Towards the middle of June 2000, the Taliban resumed its offensive, and captured the northeastern city of Taloqan. Commander Masood and commanders under the United Front for Afghanistan (UFA), also known as the Northern Alliance, continue to hold the Panjshir valley and Faizabad. The UN Secretary General's Personal Representative to Afghanistan Fransesc Vendrell engaged in extensive discussions with various Afghan parties and interested nations throughout 2000, but there was little visible progress in ending the conflict. A group of representatives from the six nations bordering Afghanistan plus the United States and Russia met several times during 2000 to explore ways to end the conflict.

A number of provincial administrations maintained limited functions, but civil institutions were rudimentary. There was no countrywide recognized constitution, rule of law, or independent judiciary. The Taliban remained the country's primary military force.

Agriculture, including high levels of opium poppy cultivation, was the mainstay of the economy. For the second year in a row, in 2000 the country was the largest opium producer in the world. The agriculture sector suffered a major setback in 2000 due to the country's worst drought in 30 years. Experts estimated that the drought affected more than half of the population, with 3-4 million severely affected. The drought affected all areas of the country, causing an increase in internal displacement, loss of livestock, and loss of livelihood. The crop loss in some areas was estimated to be 50 percent. Approximately 80 percent of the livestock of the Kuchi nomads reportedly perished, and the Argun reservoir, which supplied water to 500,000 farmers and to Kandahar, ran dry, as did 8 rivers in the region. In addition to the drought, the agricultural sector continued to languish because of a lack of resources and the prolonged civil war, which had impeded reconstruction of irrigation systems, repair of market roads, and replanting of orchards in some areas.

The presence of millions of landmines and unexploded ordnance throughout the country restricted areas for cultivation and slowed the return of refugees who are needed to rebuild the economy.

Trade was mainly in opium, fruits, minerals, and gems, as well as goods smuggled to Pakistan. There were rival currencies, both very inflated. Formal economic activity remained minimal in most of the country, especially rural areas, and was inhibited by recurrent fighting and by local commanders' roadblocks in non-Taliban controlled areas. The country also was dependent on international assistance. Per capita income, based on World Bank figures, was about $280 per year. Reconstruction continued in Herat, Kandahar, and Ghazni, areas that were under firm Taliban control. Areas outside of Taliban control suffered from brigandage.

On December 19, 2000, the UN Security Council imposed additional sanctions against Afghanistan's ruling Taliban movement (which then controlled around 95% of the country), including an arms embargo and a ban on the sale of chemicals used in making heroin. These sanctions (Resolution 1333), which took effect in one month if the Taliban did not comply, were aimed at pressuring Afghanistan to turn over Osama bin Laden, suspected in various terrorist attacks, including the August 1998 US Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. These latest sanctions were in addition to sanctions (Resolution 1267) imposed on Afghanistan in November 1999, which included a freeze on Taliban assets and a ban on international flights by Afghanistan's national airline, Ariana. Afghanistan's government reacted sharply to the new sanctions, ordering a boycott of US and Russian goods, and pulling out of UN-mediated peace talks aimed at ending the country's civil war.

In the years leading up to the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States, the Taliban provided a safe haven for al-Qa‘ida. This gave al-Qa‘ida a base in which it could freely recruit, train, and deploy terrorists to other countries. The Taliban held sway in Afghanistan until October 2001, when they were seemingly routed from power by the US-led campaign against al-Qaida.

This just it, Afghanistan’s impressive average annual growth of nine per cent from 2002-2013 has declined rapidly since 2014. According to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, annual GDP growth fell from 14.4 per cent in 2012 to 2 percent in 2013, and 1.3 and 1.5 per cent in 2014 and 2015 respectively. This drastic economic decline is mainly the result of the post-2014 international military drawdown and the year of intensified political instability that followed the 2014 election. Foreign troops once brought hundreds of millions of dollars into the Afghan economy, and their departure from 800 bases, large and small, deprives the country of what was after 2002 its largest single source of revenue. By one estimate, more than 200,000 Afghans have now lost jobs in logistics, security, and other sectors of a war-driven economy.

Heightened security concerns, political uncertainty and the erosion of the rule of law since 2014 have added to a devastating loss of confidence by consumers, producers and investors. Pervasive fears of a political meltdown have led to a surge in capital flight, with both wealthy and middle-class Afghans moving assets to the Gulf States, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and Central Asia. Afghanistan’s human capital shrank too, especially among the urban middle class that had emerged after 2001 to play a stabilizing role in Afghan politics. Hundreds of thousands of Afghans, mostly young and educated, left the country in 2014 and 2015, often to seek refugee status in Europe.

This sudden economic reversal has considerable political, security and social implications. Rising unemployment and widespread poverty is already widening the legitimacy gap between the National Unity Government (NUG) and the Afghan public, and expanding the reservoir of grievances that insurgents as well as hardline ethnic and regional players could further exploit. Unfortunately, it is not the NUG’s only pressing problem.

Moreover, the economic crisis may have been predictable, but its impact remains poorly understood and insufficiently reflected in strategic thinking and policies about the country’s future. The most revealing indication of such gross underestimation of the situation is the absence of any current, reliable socio-economic data. Three years after the economic reversal began, neither the NUG nor the international community has conducted any substantial assessment of the impact of the collapse of the war economy on the Afghan people and state.

The available figures show that the most vulnerable segments of the population are bearing the brunt of the burden. According to the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey, the unemployment rate rose from 9.3 per cent in 2011-12 to 24 percent in 2014. During the same period, the number of people who were not engaged in gainful employment increased from 26.5 per cent to 39.3 per cent of the labor force; among women, the rate increased from 42.4 per cent to 49.8 per cent. Those who manage to find work have to provide for a large number of dependents, with 47 per cent of the population under the age of fifteen. Although no such figures are available for 2015 and 2016, anecdotal evidence makes it abundantly clear that these negative trends are worsening. With Afghanistan’s estimated 32.5 million people growing by perhaps three per cent annually, adding half a million people to the work force every year, the decline in employment opportunities can only worsen.

The government’s ability to implement economic reforms is hampered by internal political gridlock, bureaucratic hurdles and pervasive corruption. Capacity constraints in most government ministries continue to adversely affect the execution of development projects. Payments are delayed to private sector contractors, suppliers and even the state’s own personnel. As of September 2016, nine months into the current Afghan fiscal year, the NUG has spent only 30 per cent of a $2.5 billion development budget. This slow pace in spending and execution is depriving a cash-starved economy of much-needed funds. Despite its many weaknesses and shortcomings, the NUG has succeeded in maintaining a degree of macro-economic stability and addressing the budgetary shortfalls it encountered in 2014. It has also raised domestic revenues above targets set by the International Monetary Fund.

While taxation rates remain low in comparison to other countries in the region, there is a widening mismatch between what the government demands in terms of revenue and the services it offers. Meanwhile the costs of doing business are increasing, and rising violence and weakening government control is exposing an already shrinking private sector to extortion and other acts of criminality, including kidnapping for ransom. Those responsible may be the Taliban, urban criminal networks or a range of other actors, some with links to the state. Domestic revenue mobilization is in fact a poor indicator of the economy’s overall health, and the current effort to raise more money runs the risk of further shrinking an already fragile and struggling formal tax base.

No aid organization – including UNAMA and USAID – has provided any meaningful data on any aspect of the effectiveness of its efforts. There are sometimes project or activity counts, but they are never related to the requirement nationally or in a given area, or to any meaningful measurement of actual output. More than eight years into a war and aid effort, official reporting consists of spin or overly-broad data that are worthless in addressing either Afghan needs or the impact of aid efforts on the conflict.

Meanwhile the costs of doing business are increasing, and rising violence and weakening government control is exposing an already shrinking private sector to extortion and other acts of criminality, including kidnapping for ransom. Those responsible may be the Taliban, urban criminal networks or a range of other actors, some with links to the state.

To conclude, despite a rise in revenue collection in 2015, the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) estimated that over half of the country’s customs revenues were lost to graft that year. Public sector appointments, including critical security sector positions, are often casualties of infighting and nepotism. All this indicates the complicity of powerful political networks at the highest levels of government, costs the state and Afghan people hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues, and curtails the delivery of even basic services. Astonishingly, corruption within the security sector extends to the sale of military hardware and ammunition to insurgents.

By: Zarlasht Sarmast

Researcher / Communications and Project Manager at Zawia Media

- 2021 Jan - 20